Image by hamburgfinn from Pixabay

[Editor’s Note: Voice search, Alexa skills, and Google Assistant have emerged as a key elements in marketing and PR for many brands. This guest post by the former head of product at Amazon Alexa provides a technical perspective on concepts of designing conversational interfaces. The technical insights are mostly relevant to interface designers. However, they will also help PR and marketing pros who are developing Alexa skills to better understand interface design theory. The end section offers specific advice on how marketing and PR professionals can build Alexa skills that meet the needs of consumers and B2B customers.]

Many experts predict that voice-activated devices will revolutionize marketing. Sales of smart speakers have exploded. More and more people use voice search. More brands are creating Alexa skills and Google Assistant actions to add features and engage customers.

However, the common consensus among users and builders of voice first experiences is that voice presents users with a unique challenge not found in visual-tactile interfaces, such as texting, mobile apps, and web sites. This challenge is called “the problem of feature discovery.” It refers to the difficulty a user experiences to “discover” (i.e., figure out) what they can and cannot do through the interface. In the case of voice, it is commonly posited that the challenge is acute because the channel of voice is not able to deliver simultaneously meaning content and affordance content. That makes it impossible for the user to consume meaning and know what to do to keep the interaction moving along.

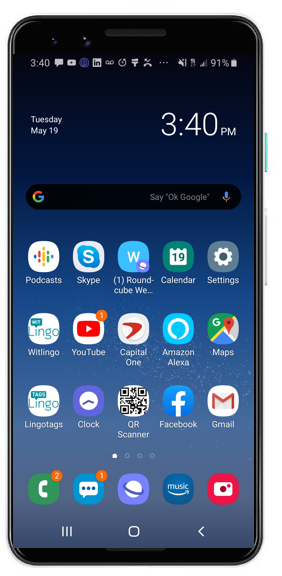

For example, looking at the home screen of my Android smartphone, I can simultaneously see what apps are installed, today’s date and time, that I have one text I have not read, and other notifications. I can also see what I can do: search Google, say, “Ok Google” to start Google Assistant, read the text, view notifications, and start Assistant.

Just looking at the screen, I can consume all of this information the screen presents and know everything I can do next.

In contrast, a voice interface cannot simultaneously answer a question and provide instructions on what I can do or say next. At best, it can first deliver the answer, and then instruct me or remind me on what I can say or do. Or less optimally, it can provide instructions first and then content (whether information, or a question, or both). In other words, the linear nature of information delivered via voice seems to decouple content information and affordance information.

So, it appears, at least in terms of affordance, the visual tactile interface is superior to the voice one.

A Second Look at the Interface

But is this really true? Is communicating affordances a tougher problem in voice than in the visual-tactile, or is the matter less obvious than that?

Let’s take a second look at my Android home screen, but let’s pretend that we had never seen a smartphone or a touchscreen before and that we’ve only seen televisions and laptops before.

What affordances would the screen naturally present? Would we know what the square meant and that we could click on them? No. The only actionable item on the screen is the imperative, “Say, ‘OK Google’.” But even then, what would we do if you were to read that? Would you really understand that it is a phrase that meant that we can speak to make something happen? Probably not.

In other words, to be able to interpret the information on the screen and act upon what we see, we must not only understand the symbols and the conventions, but established symbols and conventions must be in place that have been agreed upon by various manufacturers so that we could learn such semiotics to be able to glean content and well as actionable meaning from the shiny screen and then act accordingly. Without such an established convention and without our familiarity with it, we would be just as clueless staring at the screen as we would be upon hearing a voice assistant ask us: “How may I help you?”

Consider Human to Human Interactions

Secondly, consider how during our day to day we go about interacting with those who are near us and with whom we can speak face to face. The person with whom we are interacting doesn’t tell us the things that we can say and those that we can’t? Nor do we do the same for them.

Suppose you called your bank to wire money to a friend. You would begin the conversation with a perfunctory greeting. The agent would ask you for information to establish your identity and bank account information.

The agent will not ask you to pause so that he can recite to you all of the various things that he can do for you. You will probably not ask him: “Tell me all the things that you can do to help me?”

Both of you come to the conversation with two types of knowledge: general knowledge on the rules for properly engaging another human being in conversation, and knowledge about the types of things that one can ask a bank agent. Even though you do not have a list of everything you can ask the agent, you never really find yourself dealing with “the problem of discovery.” The discovery problem is moot.

So, how does this insight help those who ideate, design, build and market voice interfaces — solve the “discovery problem”?

I think the simple answer is that there really is no “discovery problem,” as such, that is inherent in the voice interface, but rather a problem of smuggling in our design thinking concepts that are particular to the voice-tactile UI and foreign to the voice UI.

Alexa Skills vs. Human Conversations

Let us compare human-to-human conversation to the sparse conversation with an Alexa skill. How often do you open a third-party skill with a clear goal about what you want to do and a detailed and deep understanding of what the skill can do? Probably not often. Instead, you start with a vague notion about why the skill exists, decide whether the skill is something that may help you solve a problem, and then launch it and hope for the best.

By the same token, how much does the skill know about what you want to do, how much time you are willing to spend doing it, how urgent it is for you to do it, and why you want to do it? Probably not much either. All that the skill really knows is that you may or may not have read its vague description on the Alexa skills store, and that you might be interested in using it.

When Alexa was launched in late 2014, it was able to do less than a handful of things. It was able to give you the time and the weather, play music, and answer questions as best that it could. It lacked the ability to control smart home devices, not even alarms or reminders.

And yet, the Amazon Echo was by far Amazon’s best performing device ever, outpacing in customer satisfaction, by a healthy margin, its flagship Kindle product.

Why?

Why Amazon Echo was a Marketing Success

The answer is simple. Having seen its launch video, users began their interaction knowing exactly what to expect from it. They were highly satisfied because the device gave them what they asked for and gave it to them in a novel, exciting, and delightful way. The marketers of the Echo made sure that they communicated precisely what this new gizmo could do and what it could not do, and how the user was to interact with it. In other words, both the users and the device completely understood the context of their conversation and the actions that they could take to successfully engage with each other.

What does this mean for the product managers, designers, builders, and marketers of Amazon Alexa skills and Google Assistant actions?

First, we need to refrain from describing the challenge before us as one of “discovery,” as if discoverability were an inherent attribute of the interface, but rather one that results from a basic lack of preparation work to deliver a great experience.

Second, before we begin designing, developing and marketing, we need to put in the research. It is unfathomable to me just how little research is done by most teams that launch voice experiences. They simply skip the foundation of what makes a voice experience a usable one, and start ideating on a white board, then designing (maybe) and developing.

Essential Questions to Guide Development of Alexa Skills

Here are the questions that should inform our research and information gathering:

- Why is the user launching the voice experience? The answer can’t be, “To interact with the brand ” or “To be entertained” or “To learn.” The answer needs to be something far more specific, such as: “To remove stains from clothes” (Tide), “To order coffee” (Starbucks), “To check out how stocks are doing right now” (The Motley Fool), “To get investment tips” (TD Ameritrade), “To get an update from the mayor about the latest on COVID-19” (The City of Edina), “To find my phone” (Find my Phone). The research is all about the specific things that potential users want to do.

- What will users ask when they launch the voice experience? Here, we go to the next level of detail. Someone launching an Alexa skill to remove stains will ask about stains from coffee, wine, blood, olive oil, and so forth. They will ask about how to deal with stains depending on the fabric (wool, cotton, silk), the state of the stain (just occurred or has been there for a while), and so on. We want to recruit an expert on stain removal who will not only know the answers, but also the questions, in case the user doesn’t know what questions to ask or how to present the problem.

- How will the user formulate their questions and requests? Here, we design the vocabulary and the language that will be used by users. By working with a well-defined focus, we can resolve ambiguity and understand intent. “I have a coffee stain on my tie. How do I remove it?” is perfectly understandable as an expression of the need to remove a coffee stain from a stained tie. There is no ambiguity. Similarly, “Tell me about Facebook” means, “Tell me about the Facebook stock” in the context of a stocks skill, and the latest headlines about Facebook in a headlines announcer skill, and the latest books that deal with “Facebook” the company in a book recommendation skill.

- How do I let the user know why the skill/action exists? The trick is to boil down the purpose of the skill to one sentence (semicolons not allowed). The reason why the skill exists should be boiled down to one coherent, clear sentence – or be in the name itself. (Find my Phone, Play Jeopardy). Then publish that one sentence on the store listing of the skill/action, to provide it in the opening prompt, especially for first time users and always in the help prompt: “I’m here to help you remove stains from your clothes,” “I’m here to help you track your time.” etc.

So, the next time you hear someone say, voice designers need to build for discoverability, challenge them with the proposition that the real challenge is not one of discovery through design, but one of functionality definition through solid product marketing research and iterative feature release definition and framing through sound product management.

Ahmed Bouzid, previously head of product at Amazon Alexa, is founder and CEO of Witlingo, Inc., a McLean, VA-based B2B Saas company that helps brands launch conversational voice experiences on platforms such as Amazon Alexa and Google Assistant.