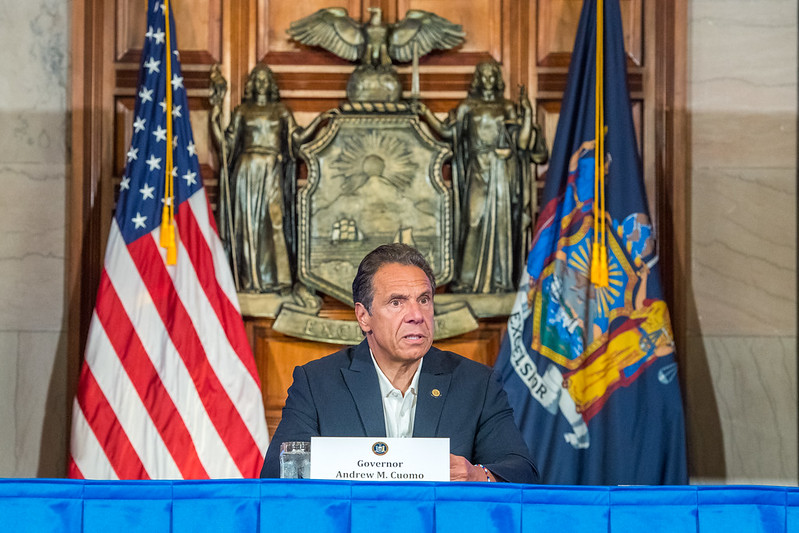

Image source: Gov. Andrew Cuomo via Flickr

On April 17, on this website, I wrote a column titled, The Dangers of Press Conferences in Public Relations. This follow-up column details more lessons that PR people can learn from the President Trump and Governor Cuomo pressers.

It’s often said from the bad, good things can be learned. That might be true in some circumstances but not, in my opinion, from the coronavirus epidemic. Some people might say that we learned we must prepare for another pandemic. But that’s not new. We learned that during past pandemics, but still didn’t prepare.

For people in our business it’s too bad that President Trump canceled his daily pressers, because there were many tuition-free lessons on media tactics employed by Trump and New York Governor Cuomo during their coronavirus press conferences. Trump’s truncated pressers should be required watching because there are still many “do not copy” lessons for PR people.

Below are several important lessons for PR people to retain in their “know it” memory;

Don’t Contradict Others

Largely because of his off-the-cuff statements and frequently contradicting the advice of medical scientists, President Trump’s daily pressers received negative media coverage. Conversely, New York Governor Cuomo’s pressers received high marks, from the media and PR people.

The governor never contradicted anything other speakers said. More important, everything he said was based on facts, not conjecture, like many remarks by the president at his conferences. The governor’s pressers always contained new approaches to lessening the spread of the coronavirus.

The president also tried to derail his medical scientists from answering questions by interrupting them.

Lesson #1 for PR people: Not permitting another featured speaker to finish a statement will result in negative coverage.

Trump often used his pressers to attack his political enemies, causing some networks to cut away from the press conference. Importantly, Cuomo always gave credit to the work of others. In fact on his April 30 conference, he handed the platform to former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, allowing him to explain in detail his new initiative with John Hopkins University to conduct contact tracing.

Lesson #2 for PR people: Before suggesting a press conference, which in my opinion is almost never, consider the news value of the presser, its purpose, and the quality of the speakers.

How Not to Deal with Reporters

Several times President Trump attempted to change the media’s news coverage by announcing new initiatives. It didn’t work.

Lesson #3 for PR people: Approach a crisis directly. Attempting to divert press coverage by announcing new initiatives will not lessen coverage of the dominant problem. The president often attempted to derail reporter’s question by chastising the journalists as “fake news.”

Lesson #4 for PR people: Belittling reporters will not change their questions. If you fear that certain questions will be asked, don’t hold a press conference. Instead, consider a setting where you can hand pick the journalists, like a round table discussion.

There were numerous leaks to the media from White House personnel that fueled reporters’ questions at the president’s coronavirus pressers.

Lesson #5 for PR people: During a major PR crisis, it’s almost impossible to keep negative information from eventually become public.

When to Hold Press Conferences

So many of the president’s pressers were devoid of news that even pro-Trump newspapers like the Wall Street Journal did not report on them.

Lesson #6 for PR people: Clients pay PR agencies for advice. If a client suggests a press conference and you feel that it lacks news, say so. That’s preferable to staging an expensive dog and pony show that results in little or no coverage. But always suggest alternative methods.

The Trump pressers often ran about two hours.

Lesson #7 for PR people: Avoid overly long press conferences. The longer a presser, the greater the possibility of a reporter asking a question not to the client’s liking. In contrast, Cuomo often limited the length of his pressers.

The length of a press conference has no bearing on how it will be covered. It’s the news value that matters. Limit the time of the formal conference, but factor in a considerable amount of time for reporters to ask speakers questions.

Reporters who are proficient at interviewing appreciate this because they can develop their own angles. Those who aren’t still could report on the presentations and the questions and answers.

Stick to the Script

Remarks by presenters at a press conference should be approved in advance and adhered to.

Lesson #8 for PR people: During rehearsals – and all pressers need full dress rehearsals – emphasize the importance of not veering from the script. Use Trump’s unexpected statement regarding disinfectants as a possible cure for Covid-19 as a teaching tool.

Unlike Trump, Cuomo takes responsibility for his actions. The president has said he feels no responsibility for the situation and blames others.

Lesson #9 for PR people: Clients who always point fingers at other individuals or entities are viewed suspiciously by the media, often leading to additional negative coverage as reporters investigate the client’s accusations.

Cuomo personalizes his experiences during his pressers in a bittersweet manner. President Trump personalizes his experiences in a feeling-sorry-for-himself manner. He has said no one gives him the credit he deserves and once said everyone is worried about people, but no one is worried about him.

Lesson #10 for PR people: Clients and PR people who feel that they are unjustly victimized by the media should never say so in public. It will lead to additional negative coverage.

On his May 1 press conference, Cuomo was asked how he thought he was doing in handling the coronavirus situation. The governor replied that he tries his best. This is in sharp contrast to the president, who daily praised and pompously applauded himself, using self-congratulatory, self-aggrandizing phrases.

Lesson #11 for PR people: When dealing with the press, never make statements that go against the facts. It always results in negative coverage.

After several days away from the press conference stage, Trump re-appeared on May 12. It didn’t take longer than a New York minute for the president to again exaggerate his accomplishments, misstate facts and assail reporters.

Lesson #12 for PR people: This might be the most important lesson that PR people should remember. Not all clients have the temperament to be questioned by journalists. How a client replies to a question can determine how the individual is portrayed by the media.

Trump conducts his press conferences in a whatever-I-say-should-be-accepted-as-I-say-it-because-I’m-the-smartest-person-in–the-world manner. Conversely, Cuomo speaks as if he was talking to you individually, expresses empathy and concern, says he accepts the advice of people smarter than he is and is not afraid to say, “I don’t know.”

As a result, Trump’s pressers have received poor grades, forcing him to cut back on them; Cuomo has made his pressers a national must watch event.

Lesson #13 for PR people: During a crisis, spokespeople should always express empathy for those affected, and never act as if they have all the answers to the problem, unless they do.

A Summary of PR Takeaways

- Press conferences can easily backfire. They should be held only when important news will be announced.

- Press conferences often disappoint a client who expects major news coverage.

- Press conferences should always include individuals who can answer questions that the principal speaker can’t.

- Press conferences are dangerous. Questions might be asked that the client doesn’t want to answer, resulting in blaming the agency for not being able to control the media.

- There are alternative methods of disseminating a client’s messages other than a press conference. PR people should always present them to the client.

- Blaming others for a problem will not deter negative press coverage.

- As negative coverage of Trump’s pressers show, the company and the title of those presenting will not impress the media.

- Clients and PR people should always appear upbeat when engaging with the press.

- Always be factual; reporters check statements.

- Prior to suggesting press interviews, consider whether the client can handle negative questions in a dignified manner.

- Regardless of the individual’s title, speaking in a know-it-all attitude is a mistake.

Cuomo’s Course in How to Conduct a Press Conference

The New York governor gave a master’s course in how to conduct a press conference. Two highlights merit extra mention:

On May 3, Cuomo announced a consortium of Northeastern governors who agreed to work together to purchase medical equipment. Unlike Trump, who insists on dominating his engagements with the media, Cuomo yielded his platform to the governors of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Connecticut and Delaware. In addition, he praised the governors of Rhode Island and Massachusetts, also members, who did not appear on the telecast.

On May 17, when he urged people to have themselves tested for the coronavirus if they had one of several symptoms, he had himself tested on national TV to demonstrate how simple, easy and fast the test is.

Letting others share the spotlight will not diminish the role of a client; indeed, it will make the person appear generous and humble. If a client wants to take a leadership position on a topic, actions are more important than words.

Nothing is Off the Record

While this column zeros in on the Trump and Cuomo press conferences, many of these lessons apply to any type of engagement with the media. PR advisors should remind clients that in all circumstances, even when a reporter puts his tape recorder or notebook away, that anything said after the formal interview or press conference can be used by the journalist.

And PR people and clients should remember that nothing is off the record forever. Even if a reporter agrees not to use remarks made during an interview, they might show up in a future story.

When I was a journalist, if a person told me, “I’ll tell you something if you won’t use it,” I would respond, “If you don’t want to see it in print, don’t tell me.”

Don’t say it if you don’t want to see remarks that you’ll regret saying in stories is a rule that PR people and clients should always remember.

Arthur Solomon, a former journalist, was a senior VP/senior counselor at Burson-Marsteller, and was responsible for restructuring, managing and playing key roles in significant national and international sports and non-sports programs. He now is a frequent contributor to public relations publications, consults on public relations projects and is on the Seoul Peace Prize nominating committee. He can be reached at arthursolomon4pr@juno.com or artsolomon4pr@optimum.net.